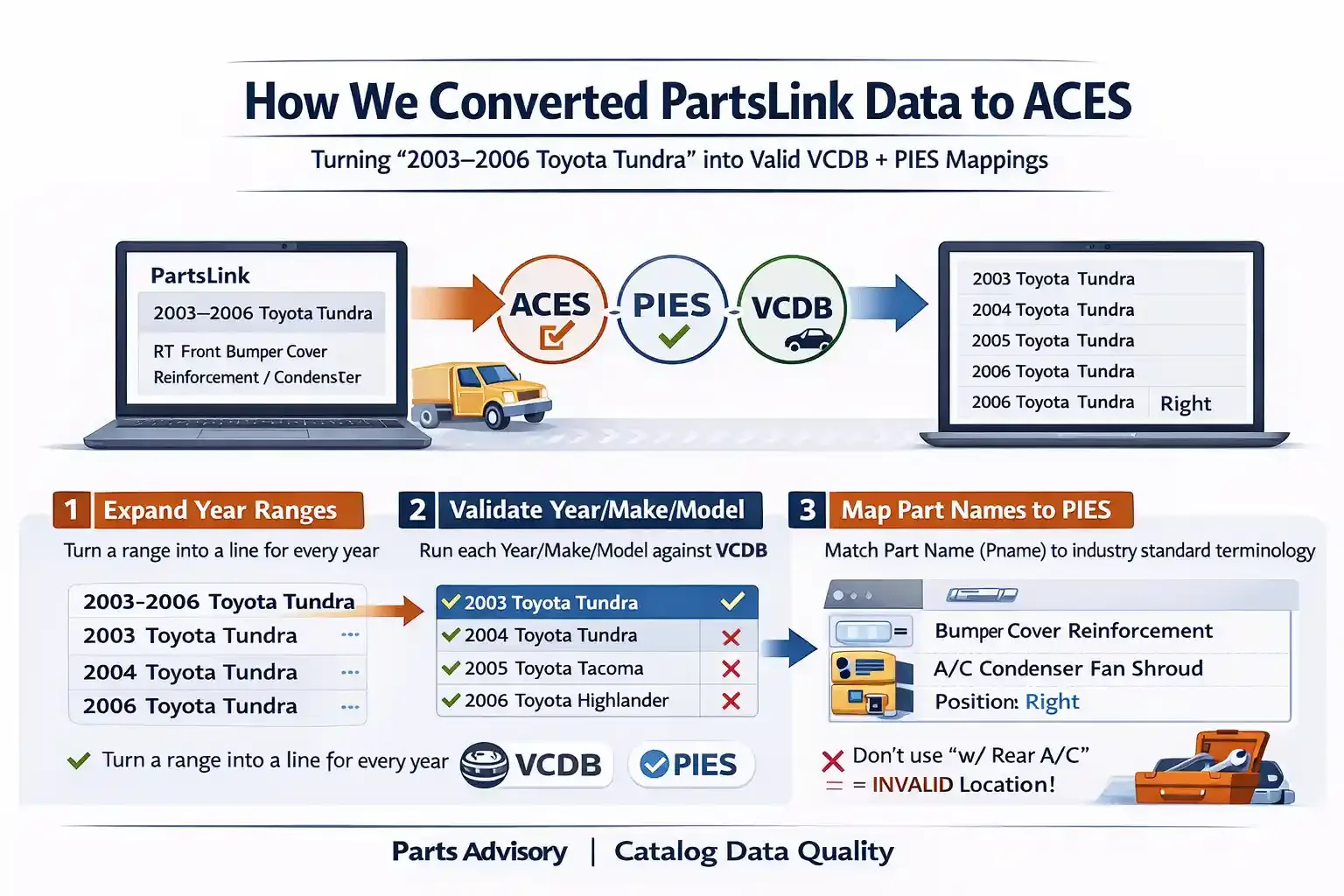

How We Converted PartsLink Data to ACES

Turning messy year ranges + names into valid VCDB + PIES mappings

PartsLink-style data is useful - but it’s not ACES-ready out of the box.

A typical PartsLink record gives you a year range and a make/model, like:

2003-2006 Toyota Tundra

That looks clean, but to publish ACES you need a system that produces:

one row per year (or at least expandable year coverage)

valid Year/Make/Model combinations against VCDB

a mapped Part Name to a valid PIES PartTerminologyName

consistent location + qualifiers using rules (not guesses)

and, when notes include it, the right attribute stack (engine/trans/body) without “inventing” data

This is the workflow we used.

Step 1 - Expand year ranges into one line per year

PartsLink often provides year ranges like:

2003-2006 Toyota Tundra

The first automation expands that into individual years so it can be validated and normalized:

2003 Toyota Tundra

2004 Toyota Tundra

2005 Toyota Tundra

2006 Toyota Tundra

This sounds simple, but it’s the foundation. If you don’t expand years, you can’t reliably validate coverage or detect invalid combinations.

Step 2 - Validate Year/Make/Model against ACES VCDB

Next, we run every Year/Make/Model through VCDB validation to confirm the combinations actually exist.

This step is where a lot of rows fail - and that’s normal.

Once you scale this across a PartsLink dataset, you’ll often see thousands of failures, because:

make/model naming is inconsistent

model names don’t match VCDB exactly

“marketing” names show up instead of official VCDB model names

trims/submodels get mixed into the model field

This step forces reality: if it’s not a valid VCDB combination, it can’t be used in ACES without cleanup.

Output of Step 2

✅ Pass list (VCDB-valid Year/Make/Model)

❌ Fail list (needs normalization rules or manual exception handling)

Step 3 - Map Part Names (Pname) to PIES PartTerminologyName

This is the part that surprises people: the Part Name in PartsLink data is rarely PIES-ready.

We had to map every Pname to a valid PIES PartTerminologyName.

Example

Pname: RT Front Bumper Cover Reinforcement / Condenser Fan Shroud

PIES PartTerminologyName: Bumper Cover Reinforcement / A/C Condenser Fan Shroud

Almost all part names need mapping. In our case, it was roughly ~40 core part types (one-to-one mappings), like:

Steering Wheel

Windshield Frame

Engine Mount

Air Cleaner Assembly

Fuel Tank

…and more

The key is to treat this as a controlled dictionary, not free text. If terminology isn’t standardized, everything downstream becomes guesswork.

Step 4 - Extract location + qualifiers using strict rules (not interpretation)

After part terminology is mapped, the next step is extracting location and qualifiers.

This requires very clear rules, because abbreviations can be misleading.

Example rule

If “LT” appears in your variables column, it may not always mean “Left.”

But if “LT” appears in the Pname column, in our dataset it did mean Left.

Another rule

Don’t treat

w/ Rear A/Cas a location value.

It’s a qualifier, and it should be handled separately.

If you don’t lock these rules down, location becomes inconsistent fast - and your ACES output becomes unreliable.

Step 5 - Notes and the “attribute stack”: extract clues, then let VCDB decide

This is where a lot of ACES conversions quietly go wrong.

Don’t try to “compute” EngineBaseID / Aspiration / Fuel from note text.

Use the note text to extract clues (liter, maybe cylinders, maybe turbo), then let VCDB decide by filtering valid configurations for that exact BaseVehicle.

You’ll see note patterns like:

Raw note: 2.0L; A/T; Sedan/Wagon

(example: 2009 Audi A4)

5.1 Parse the note into clues (not final IDs)

Clues you can safely extract

Liter: 2.0

Transmission control: Automatic (A/T → Automatic)

Body types: Sedan, Wagon (multi-value)

Clues you should NOT assume unless explicitly present

Cylinders (unless the note has I4/V6/V8)

Aspiration (unless note has Turbo/Supercharged/NA)

Fuel type (unless note has Diesel/Gas/Hybrid/etc)

Even if you “know” Audi 2.0 is often turbo, you’ll eventually get burned by edge cases (diesel trims, multiple engines with the same liter, etc.). Let VCDB narrow it.

5.2 Engine: filter VCDB configs for that BaseVehicle using the clue(s)

For (2009 Audi A4) the flow is:

Resolve BaseVehicleID from (Year, Make, Model)

Pull valid VCDB configs for that BaseVehicle (example relationship:

BaseVehicle → VehicleToEngineConfig → EngineConfig → EngineBase/Aspiration/FuelType)Filter in this order (deterministic):

Engine filter order

Liter match (2.0)

Cylinders match (only if you parsed it)

Aspiration match (only if you parsed “Turbo”, etc.)

Fuel type match (only if you parsed “Diesel”, etc.)

Decision rule

If exactly 1 config remains → select it and output:

EngineBaseID, Liter, Cylinders, AspirationID/Name, FuelTypeID/NameIf 2+ configs remain → don’t guess. Either:

output multiple rows (one per engine config), or

route to an exception queue (“needs more tokens / human review”)

That’s how you avoid silent wrong mappings.

5.3 Transmission: treat A/T as control type, not a full transmission definition

From A/T you can confidently set:

TransmissionControlTypeName = Automatic

But you cannot infer:

TransmissionNumSpeeds (unless the note says “6-speed”, “8AT”, etc.)

So the rule is:

If speeds not present → TransmissionNumSpeeds = null

You can optionally enrich later using VCDB configs, but don’t force it from the note.

5.4 Body type: the hardest field to automate

Your note says: Sedan/Wagon

That should usually become two output applications (or two body-type-scoped records), not one.

Practical body-type rule

If note explicitly lists multiple body types (Sedan/Wagon) → split into multiple rows

If note has a non-sedan (Wagon, Hatchback, Coupe, Convertible, Van, Crew Cab…) → require a VCDB match

If note only says “Sedan” → allow sedan-only OR “sedan default” depending on your strategy

The trick that keeps this scalable

For the BaseVehicleID, pull every BodyType VCDB says is valid, then compare to what your note contains.

Your debugging idea is exactly right:

For a given BaseVehicleID, print every BodyType except Sedan

That gives you a “non-sedan dictionary” per model that you can iteratively map.

Why it’s hardest

note vocabulary is inconsistent (Wagon, Avant, Sport Wagon, Touring, etc.)

VCDB body types can be normalized differently than raw text

some models have body style overlap across submodels/doors

Step 6 - QC checks before you publish ACES

Before output, we ran checks that catch the majority of problems early:

Duplicate detection: same app covered twice (overlapping rules)

Conflicting qualifiers: Left + Right in the same record

Coverage sanity: missing years inside a range (“holes”)

Exception review: rows where VCDB filtering returns multiple valid configs

Spot checks: sample vehicles and confirm expected fitment behavior

The point isn’t perfection - it’s repeatability. If a rule is wrong, you fix it once and the dataset improves.

Why this workflow works

This approach turns PartsLink-style inputs into something you can actually publish:

ACES output that matches VCDB reality

PIES-ready terminology with a controlled mapping table

qualifiers that are consistent because they’re rule-driven

fewer returns caused by “interpretation” errors hidden in free text

If you’re sitting on PartsLink-style data and trying to publish ACES without creating a manual cleanup nightmare, this workflow is the difference between “almost works” and “actually scalable.”

If you have PartsLink “VARIABLES” data and need ACES-ready output

If you’re working with PartsLink-style data, you already know the hard part isn’t getting the file - it’s turning VARIABLES into something you can publish in ACES without guessing.

In our workflow, VARIABLES can contain a near-complete set of signals - location, configuration, and fitment qualifiers - but only if they’re converted with a controlled mapping and validated against VCDB.

If you have (or can provide) an almost complete list of what shows up in your VARIABLES column - and you want a clean, deterministic translation into ACES fields (and/or the broader VCDB attribute stack like body, drive, transmission, engine, aspiration, fuel) - I can help you:

build a full VARIABLES → ACES/VCDB mapping dictionary

define the rule order (so tokens don’t collide or get misread)

validate everything against VCDB so the output is publishable

set up an exception queue for edge cases instead of silent wrong fitments

deliver a repeatable process you can run on every refresh (not a one-time cleanup)

If you want to sanity-check how strong your mapping is, send me:

20-50 real VARIABLES values (messy is fine), and

one example of the “ideal” ACES output format you want.

I’ll tell you exactly what can be automated cleanly, where VCDB filtering is required, and where the remaining risk lives - before you scale it across the full dataset.